Religion in a Plural Society: Indonesian Perspectives

Text: Claudia Seise

The idea for the virtual exhibition came up spontaneously during a meeting with Dr Saskia Schäfer, Dr Thomas Stodulka, and Prof Mohammad Gharaibeh, when we discussed the project Democracy and Interreligious Initiatives, funded by the Berlin University Alliance. As with many other projects, Covid19 (Corona) had forced the members of our project group to explore new, alternative, and creative ways to be able to breathe life into the project despite the new, limiting circumstances, and to present interesting results. That was when the idea for a virtual exhibition came up. I have been engaged with modern Indonesian art since my study visit in Yogyakarta, Java, in 2005/6 and I carried out an independent field research on contemporary Indonesian art in Yogyakarta in 2008/9. The results were published in the book One Year on the Scene: Contemporary Art in Indonesia (2010). In my further research work I then got more and more involved in the topic of Islam in Indonesia. The virtual exhibition Religion in a Plural Society: Indonesian Perspectives now brings together these research interests: art and religion, art and spirituality, art and Islam.

The artworks of 14 artists with different geographical, religious, and artistic backgrounds are shown in this exhibition. When choosing the artists, I tried to reflect on the fundamental importance of diversity in the Indonesian archipelago. Four of the 14 artists are women. In Indonesia, often men become artists, while women rarely study art. The majority of the 14 artists have a Muslim background, which reflects the society of Indonesia. Four artists either have an Evangelical or Hindu background or follow a Javanese belief system. The artists come from Java, Sumatra, Bali, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi. In addition to painting, the exhibition also includes graphic art, glass painting, and sculptures.

With this virtual exhibition, I hope to make a creative contribution to science communication that is not limited to summarizing scientific results, but rather focuses on active listening and observing. Adding an artistic perspective to research on inter-religious initiatives in Indonesia, expands the expertise on inter-religious commitment and understanding of democracy in connection with religion. The crossing of linguistic boundaries through visual art offers the possibility of new bridges and communication channels. In this spirit, the exhibition Religion in a Plural Society can also be perceived as a research instrument. I would like to thank the Berlin University Alliance and Dr Saskia Schäfer for the opportunity to organize and curate this virtual exhibition. Special thanks go to the 14 artists, who put their time and creative energy in this project. Terimakasih banyak!

Indonesia

Indonesia is an insular state in Southeast Asia, bounded by the Indian Ocean to the west and the Pacific Ocean to the east. It lies on the Pacific Ring of Fire and has one of the highest volcanic and tectonic activities in the world. The country stretches from the northernmost tip in Sumatra, Aceh, to West Papua and includes more than 17,000 inhabited and uninhabited islands. Home to a wide variety of ethnic, religious, cultural, and linguistic groups, Indonesia has existed as a nation state since August 17, 1945. It combines the above-mentioned diversity in the national motto Bhinekka Tunggal Ika, unity in diversity, within the state ideology Pancasila.[1] The first pillar of the Pancasila is the belief in the One and Only God. The vast majority of Indonesians consider themselves Muslim. Christians, Catholics, Hindus, Buddhists, followers of Confucianism and local belief systems (Ind.: kerpercayaan) can also live their faith openly. In some areas of Indonesia, different religions, perceived as minorities on the national level, represent the majority. For example, in Bali where most of the residents follow Balinese Hinduism. The reference to the Indonesian national ideology is also made in the artworks of some artists in this exhibition and is understood as an important basis for national harmony and tolerance of religions. In the concept of her work “Tree of Life”, the artist Budiasih describes the Pancasila as a vessel that becomes a tool to connect religions and beliefs in Indonesia in order to achieve ideal coexistence. The graphic artist Syahrizal Pahlevi also refers to the Pancasila in his work “6+1 ID Card”: the first pillar of the Pancasila, the belief in the One God, de facto states that all Indonesians must register their religious affiliation on their ID card. According to the artist, this means that the religious affiliation of every citizen must be made public. The artist is convinced that this can also lead to discrimination based on religious affiliation. The artist Robert Nasrullah also connects his work “Ta’aruf: Getting to Know” with the Pancasila and perceives it as a sort of umbrella under which all religions and belief systems in Indonesia enjoy the state’s protection.

Religion, faith, and spirituality are profound elements of Indonesian life. Prayer, connecting to the invisible world, spiritual practice and deeply rooted faith are an important part of the life of many Indonesians. At the same time, belonging to a religion or a belief system is traditionally seen as a prerequisite for learning the virtues of tolerance and respect for those of different faiths to become part of a harmonious togetherness. It is assumed that the geographic location of the archipelago has contributed to openness and tolerance towards new and different ideas. Located on the maritime Silk Road, today’s Indonesia is located on historically grown trade routes that connected the archipelago with the Arab world, Africa, Europe and possibly even with South America. In the concept for his sculpture “Dialogue”, the artist Sindu Siwikkan states that he is convinced that the geographical location contributes to the fact that Indonesians are generally very curious and open towards other people. Furthermore, he sees tolerance towards religious practice and plurality in origin, religion, and language as its result and this is deeply rooted in Indonesian society. Despite this tolerance mentioned by several artists, there are also conflicts and as mentioned by Syahrizal Pahlevi, discrimination in Indonesian society. However, this does not negate the inherent pursuit of harmony (Ind.: kerukunan), which is also expressed through the Pancasila and the recognition of any faith that leads to the One God. It is the deeply rooted pursuit for harmony, which allowed for new ideas, belief systems, and religions to enter the societies of the archipelago. Then be adapted to local circumstances, traditions, and ideas. In this regard, the people of Indonesia are very receptive, but also extremely careful to maintain their cultural, spiritual, and religious freedom, independence, and authenticity.

Religion in Public Space

Since my studies in 2005-2006, I have lived, researched, and worked in Indonesia for a total of more than five years. During this time, it became very clear to me that religion, belief, and spirituality in many different facets are an important, integrative, and indispensable part of Indonesian society. The publicly practiced faith is not expressed in a homogeneous way. This is also true for Islam, the majority religion in many parts of Indonesia. In her work “Twilight at the Harbour”, the artist Rina Kurniyati wants to express the diversity of cultures, religions, and profane life in Indonesia. 15 separate glass paintings, which show different types of cars in different colours, form together one artwork. Every single picture can be observed separately and is a coherent work in itself. However, all 15 pictures with all 15 types of cars can also be viewed together as one artwork. A work that impresses with its variety and play of colours, and in which every single car blends into a total work of art. The symbolism is profound and yet so simple. In her concept Rina writes: “Ultimately, my work shows that it depends on the end result: a time when everyone comes together to respect one another. Every element of society shows and lives its uniqueness, because the real essence of mutual respect is the existence of differences and the beauty of the different colours.” The artist Robert Nasrullah describes this phenomenon with a different analogy, namely that of the white canvas, which is painted with different colours. By using different colours, a beautiful and meaningful work can be created, according to the artist. “Through the artistic process, we indirectly learn that different (religious and spiritual) beliefs are no obstacle for us to stick together and help each other,” says Robert Nasrullah in his concept for “Ta’aruf: Getting to Know”. Artist Fika Ariestya Sultan also finds a suitable analogy for the religious and spiritual diversity in Indonesia: the flower meadow that he depicts in both of his works. He writes: “People are perfect like the different flowers in a meadow. Their different sizes and blooms make them beautiful and complementary. Plurality is wonderful when it is based on a broad understanding of love (Ya Rahman) and deep love (Ya Rahim).”

In Indonesia, prayer houses of different religions are sometimes located in close proximity to each other and shape the religious public space. An interesting phenomenon are mosques built in the traditional Javanese form of a pendopo, a pavilion-like building on pillars, without a minaret or cupola. The pendopo is a basic part of Javanese architecture and is traditionally a place for rituals and religious ceremonies, but is also used to receive guests. The pendopo can stand alone or be part of a traditional Javanese house. It is an interesting example of how the localization of Islam in Java’s public space has been realized in the form of mosques in traditional architecture. Some form of pendopo can be found in many mosque compounds. The typical Javanese pointed roof, which resembles temples, can also be found on many traditional mosques in Java, but also in Sumatra, e.g., in Palembang. The great Mesjid Agung Mosque in Kota Gede, Yogyakarta on Java, and the Mesjid Agung in Palembang, South Sumatra are interesting examples for the realization of the traditional Javanese roofs.

Besides prayer houses, people also reflect faith and spirituality in public spaces. Many women wear the headscarve (Ind.: jilbab) and thus consciously and confidently show that they belong to Islam. One can also see Muslim men wearing the typical headgear, peci. Christians often wear a cross, and Hindus wear religious symbols as well, e.g., grains of rice on their foreheads, which are pressed on with water after their traditional prayer. During official public events, different salutations are used with the aim to reflect religious diversity, e.g., Assalamualaikum, the Islamic greeting, Salam Sejaterah, the greeting for people of Christian faith, and Om Swastiastu for followers of Balinese Hinduism.

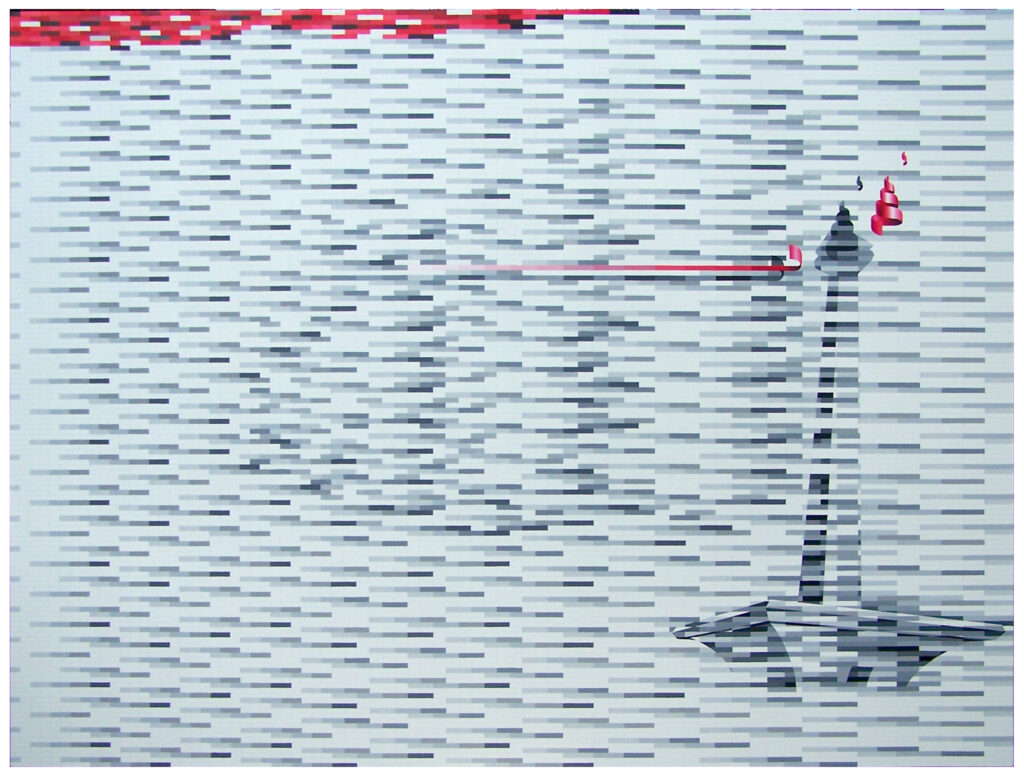

With his artwork in lacquer technique, the artist Suparman reflects on the diversity of the different cultural and spiritual currents in Indonesia by displaying a cultural festival. Figures wearing traditional masks and costumes dance together in the capital city of Jakarta. In the background, one can see an important symbol of the Indonesian nation, the National Monument (Monas). It symbolizes the struggle for independence and can be read as a symbol of the unity of Indonesian diversity. Friedrich Silaban and R.M. Soedarsono designed the Monas monument. On the right side of the picture, one can also see the Dirgantara monument, also known as the Pancoran statue. The Indonesian artist Edhi Sunarso designed it and it was completed in 1966. This second statue symbolizes the technological progress of the Indonesian nation, especially in relation to aerospace technology.

The national monument Monas is such a central symbol of the Indonesian nation that it represents a key element in the public space and in the collective consciousness of the Indonesian population. It is repeatedly referred to in the religious and non-religious sphere, and charged with personal and religious interpretations. For example, the Indonesian artist Askanadi, who does not take part in this exhibition, has interpreted the national monument as a symbol of the religiosity of the Indonesian population. The pillar pointing upwards stands for the vertical connection to God and the receptive, lightly bowl-like foundation stands for the Indonesian people. Regardless of which religion or belief someone belongs to, they all unite in the receptive, horizontal part of the monument in their vertical connection to God. (Image)

A commonly accepted interpretation of the monument, inspired by Hindu tradition, is the symbolism of the lingga, which cosmologically stands for the male element, and yoni, which stands for the female element. From an Islam-theological perspective, in my opinion, the Monas Monument can also be interpreted as the Arabic letters Alif and Ba. According to the science of the symbolism of Arabic orthography, the Alif symbolises the descent of the Divine Word from the world of Divine Transcendence. Ba symbolizes its reception in the human world and in human language, which is thereby sanctified (In: The Study Qur’an; Nasr, 2015: xxxiii). The foundation in the receptive element can also be interpreted as the dot under the Arabic letter Ba, which symbolizes the meeting place of the two letters Alif and Ba: where the vertical dimension, the connection to God, and the horizontal dimension, the reception of the word of God in the human world, come together. The vertical and horizontal dimension in relation to the Divine and the experience of the Divine in this world also comprises a theme in some of the artworks in this exhibition.

The artist Ariyadi alias Cadio Tarompo, for example, points to the vertical and horizontal connection between humans and the Creator and creation, and especially humans. In his work “Hablumminallah wa Hablumminannas”, he explains the Islamic perspective and points out fundamental values of Islamic teaching: 1. there is no compulsion in religion (Quran 2: 256) and there is a need for mutual tolerance of followers of different beliefs (Quran 109: 6). He also sees the Indonesian state ideology Pancasila as a necessity in order to preserve and protect religious diversity in Indonesia.

Nature and Spirituality

Nature in all its richness, fascination, and threat to human life plays a special role in Indonesia. Volcanoes, the architects of the world who gift people fertile earth, the sea, the rice fields, rivers and stream courses, mountains and forests, and the rich flora and fauna are not only the backdrop for human life, but also spiritual and public spaces of actively lived faith. However, love and respect for nature is not to be put on a level with worship and an ascription of Divine causality. Often misinterpreted as animism by orientalists, the deep connection with nature is based on a deeply rooted, inter-generational understanding of the first pillar of the Pancasila, the belief in the One and Only God. The various components and beings of nature, in Javanese tradition are referred to as siblings (sedulur) of human beings. Human beings respect them and can learn from these cosmological siblings, because in cosmological reality they are older than human creation. Accordingly, humans should aim to coexist in harmony with the various components of nature. Since in Indonesian and especially in the Javanese tradition, respect and veneration are primarily linked to age, the older siblings in nature receive special treatment. This is not to be confused with worship. The ‘dressing’ of large, old trees with cloths, for example, is an expression of respect for the elderly member of the family of creation.

Coexistence and the horizontal connection of humans with the rest of creation also play an important role in the work of I Wayan Legianta. He explains that God is present in every living being through the Divine Soul called Atman, in Balinese Hinduism. He further writes that Atman can be understood as a small spark of God that gives life to every living being, including humans. Therefore, according to I Wayan Legianta, it is very important to respect and appreciate every living being and the diversity in Creation. It is this appreciation of creation that leads to the glorification of God Himself. His work of art reflects these thoughts. Different shades of colours, notches and layers harmoniously fit into a whole. The merging of colours and forms is supposed to hide the particular religious identity and to allow each person to be seen as a ‘being of faith’. No matter what faith a person follows, everyone pursuits the vertical connection with God.

Franziska Fennert also reflects the horizontal connection with creation and the vertical connection with the Creator in her work “Healing”. With her work, the artist points out the responsibility of humans towards the environment and all other creatures. According to the artist, every element of the cosmos testifies to the existence of God. The semi-circular shape of the work resembles a church window and thus symbolizes the Divine. Human’s responsibility towards nature is also spiritual, both in traditional Javanese spirituality and in Islam. In this way, I propose that the spirituality of the natural space (nature) becomes the spirituality of the public space of nature.

Personal Faith and Spirituality

Religion, belief, and spirituality also play an important role in the life of the individual and influence society through this person, their actions, their behaviour, their interaction, their words, etc. In this way, the individual on a micro level shapes the public space. In his artwork “Self-Reflection”, the artist Anggara Tua Sitompul reflects the importance of acquiring money in a religiously permitted framework so that it is also beneficial and blessed. In his concept, the artist expresses his criticism as a surprise that many religious people steal and misappropriate people’s money. His conclusion: many people are religious but not pious. Although they are followers of a religion, they do not implement the teachings of that religion in their own lives.

In his work “Vertical Knot”, artist Rudi Maryanto also reflects on his own religious affiliation and places the symbol of the Islamic direction of prayer, the Kaaba, at the centre of his work. Other religions and belief systems also have deeply rooted symbols that represent them in public spaces and collective consciousness.

The artist Laila Tifah describes the influence of every individual in society in her artwork “Not…”. She compares humans to an iceberg, of which only the tip is visible to everyone else. This visible part is reflected by our body language, our behaviour and our actions and decisions. Most of the iceberg is invisible. The invisible part determines how we act, behave, and make decisions. In her work, the word ‘not’ receives a positive connotation when it is combined with negative qualities, which allows preserving harmony in Indonesian society. For example, to not feel self-righteous, to not prevent other people from worshiping, to not be intolerant, to not suppress, to not be arrogant.

The artist Muhammad Andik introduces another important aspect into the discussion about religion and belief in a plural society, namely religious education. In his artwork “The Murshid (The Spiritual Teacher)” the artist reflects on the importance of a spiritual teacher for a person’s spiritual development from an Islamic perspective. In his work, we see a traditionally dressed person sitting among a group of disciples. The colour scheme, the pointed arches in the background and the traditional Sufi clothing appear mystical and the observer wonders what is being taught and learned there. In his concept, Muhammad Andik writes: “It is a murshid‘s duty to teach the salik (the knowledge seeker) who is serious about getting to know God, to understand the spiritual paths to God, to guide him/her, to educate and mould his/her soul. The murshid leads the salik with determination and discipline. This path begins with the process of purification/catharsis of the soul (tazkiyah al-nafs) until the salik comes to a deep understanding (ma’rifat) of Al-Haqq (one of God’s names).”

I end my brief comment on this exhibition by emphasizing the importance of education. I hope that visitors of this virtual exhibition will enjoy observing the artworks in addition to reading the concepts. I hope that this exhibition can make a small contribution to inter-religious dialogue and understanding. Although Indonesian society is not perfect, the desire and pursuit of harmony is a special quality that is cultivated, regardless of religion or creed. In their concepts, some artists have pointed out that ideas and ideologies ‘imported’ from outside sometimes try to attack the pursuit of harmony and the deep-rooted tolerance towards those who think differently and those of different faiths. This reality reminds us of the importance to preserve, cultivate, and teach the historically grown and established tolerance and openness and to pass it on to the younger generation.

Claudia Seise holds a PhD in Southeast Asian Studies and is currently working as a PostDoc researcher in the junior research group “Perspectives on Religious Diversity in Islamic Theology” at the Berlin Institute for Islamic Theology at the Humboldt University of Berlin.

[1]Pancasila is the state ideology of Indonesia. It consists of five principles, which are mentioned in the preamble of the Indonesian constitution:

- The belief in the One God (Ketuhanan Yang Maha Esa)

- Just and civilized humanity (Kemanusian yang adil dan beradab)

- National unity of Indonesia (Persatuan Indonesia)

- Democracy guided by the inner wisdom in unanimity resulting from the consulting of the delegates (Kerakyatan yang dipimpin oleh hikmat kebijaksanaan dalam permusyawaratan/perwakilan)

- Social justice for all people of Indonesia (Keadilan Sosial bagi seluruh masyarakat Indonesia)